Author’s note: I gave a speech about Operation Downfall in the spring of 2017 at the USS Silversides submarine museum in Muskegon, Michigan. I spent months pouring through historical documents and reading books on the proposed invasion.

After the speech, I moved on with my life.

I recently rediscovered my “Downfall folder” hidden in a backup storage drive and, after an informal poll on Substack asking if anyone would be interested in this topic, I resolved to produce what you are about to read. Suffice it to say, the response to my poll blew me away.

Apparently, there is a lot of interest in Downfall.

A large portion of my research is thanks to the incomparable book on Downfall called “The Invasion of Japan” by John Ray Skates.

Many of my other sources are linked directly throughout the text.

I normally cover the Ukraine War and other contemporary global security topics – but I do have a passion for WWII history. I also plan to make a video on Downfall for my YouTube channel, so please subscribe if you’re not already.

Finally, thanks for your support. This is an incredible community. As a veteran of both the U.S. Army infantry and the U.S. Air Force during the Global War on Terror, the concept of Downfall is an infantryman’s nightmare made manifest.

With this speech-turned-article (soon to be turned-video), I hope to have added something unique to the conversation. I’ve also sought to strike a balance between a deep historical analysis and an accessible, enjoyable read. There are people far more qualified than me to do a deep dive into Operation Downfall.

Except for the first one (1LT Stu Alley), the vignettes in italics are my original creations meant to provide some color to the events.

Stay Frosty and Слава Україні.

Wes O’Donnell – August 2024

Marine Corps fighter pilot 1LT Stuart (Stu) Alley sat on the gull wing of his F4U Corsair while fidgeting with his cowboy boots.

Not exactly government-issued flight gear, but the boots reminded him of home in North Texas and helped fuel his persona as a gunslinger.

Just then, 1LT Alley’s wingman popped up from under the wing and snapped a picture.

“For posterity, Stu. We’re probably going to die tomorrow.”

Gallows humor at its finest.

The flight over to Kadena airfield from the USS White Plains (CVE-66) was uneventful enough, but he had heard the Japanese were getting desperate… And desperate men do dangerous things.

It was April 9th, 1945, and his 24-bird unit, Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 323 – the Death Rattlers – was here to support Operation Iceberg during the Battle of Okinawa.

Just three days earlier, the Japanese launched a coordinated kamikaze assault on the U.S. Navy's Fifth Fleet off the coast of Okinawa.

They called it Operation Ten-Go.

The first attack lasted five hours and involved 355 kamikazes and over 300 fighter escorts. The Japanese called these large-scale attacks “kikusuis” which means “chrysanthemums floating on water”.

The suicide planes sank the USS Bush (DD-529) and USS LST 347.

USS Emmons (DMS-22) and USS Colhoun (DD-801) were so damaged that they were later scuttled.

Amongst the confusion, numerous U.S. ships were damaged by collision and friendly fire. A sailor buddy of his described it as the end of the world.

The concept of a kamikaze attack was completely alien to the young Marines on Kadena.

1LT Alley pondered the mindset of a suicidal pilot.

“I mean sure, if you know you’re going down and have the opportunity to take one of the bastards out with you, then go for it. But to set out knowing that you were going to die? It just doesn’t seem right.”

1LT Alley finished putting on his boots and hopped off the wing to catch up with his team.

Between April and the Japanese surrender in September, the Death Rattlers racked up 124 Japanese planes shot down without a single loss – the highest total of any squadron during the battle for Okinawa.

Twelve Death Rattlers became aces, including my grandfather, 1LT Stuart Alley.

History often hinges on the narrowest of margins.

Entire nations can rise or fall based on decisions made under the pressures of the moment.

But what if those decisions had gone the other way?

What if Archduke Franz Ferdinand had survived the assassination attempt in 1914?

What if John F. Kennedy had lived to complete a second term?

And most intriguingly, what if the United States had not dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945?

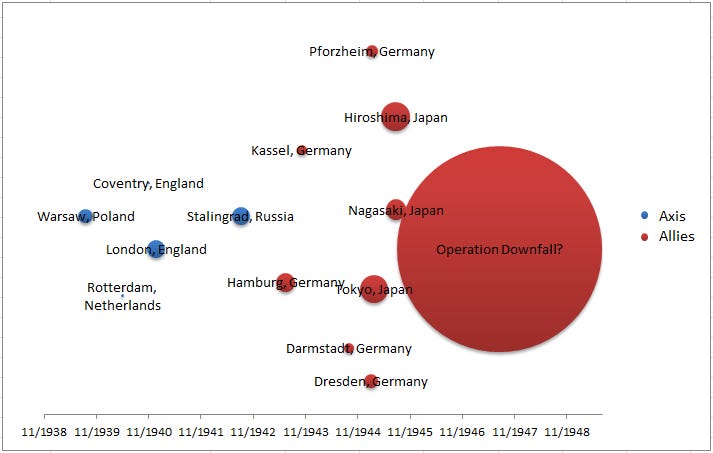

The world would have witnessed Operation Downfall, the Allied invasion of Japan—an operation that, by all accounts, would have been the bloodiest amphibious assault in human history.

Operation Downfall was the codename for the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of Japan near the end of World War II.

The planned operation was abandoned when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet declaration of war.

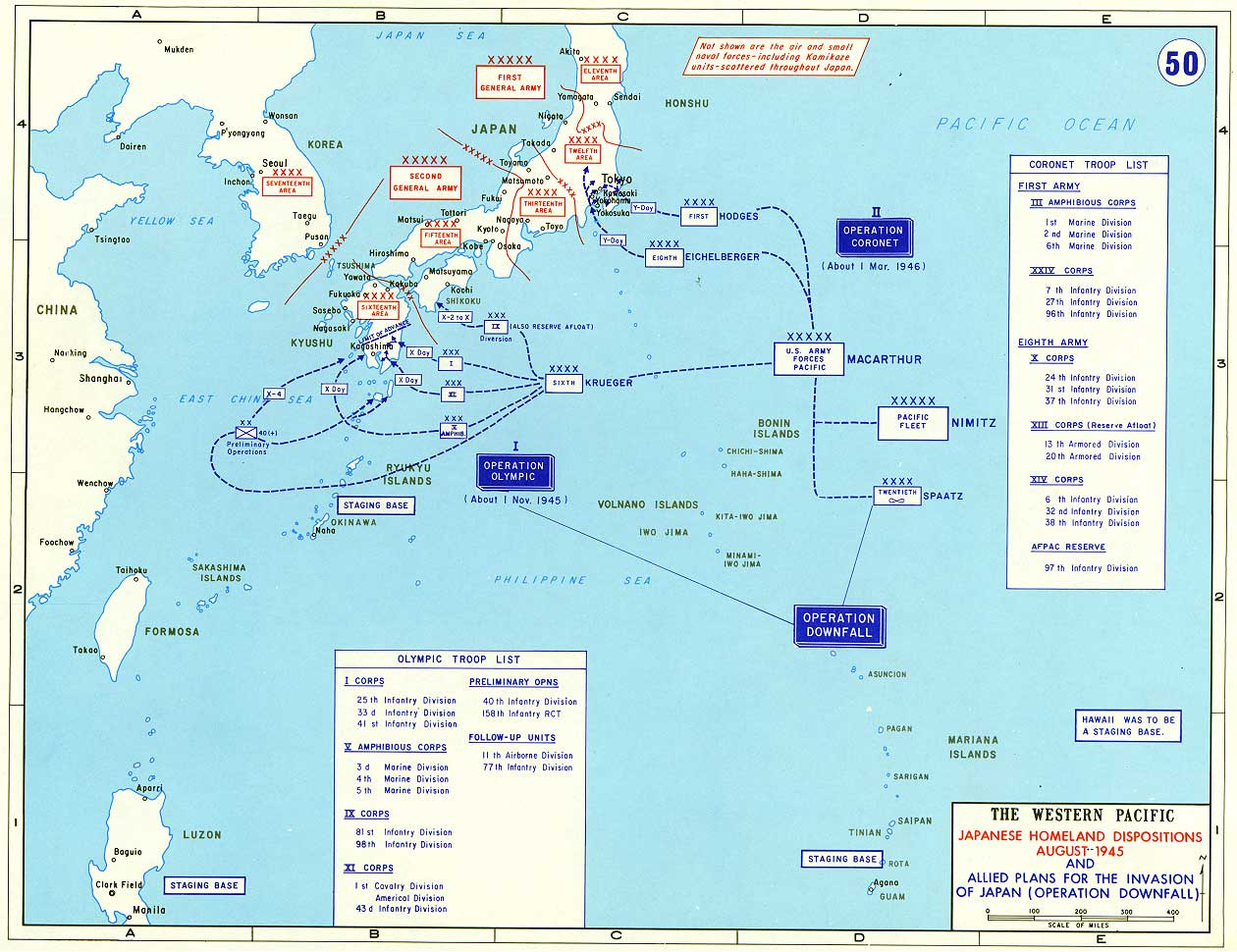

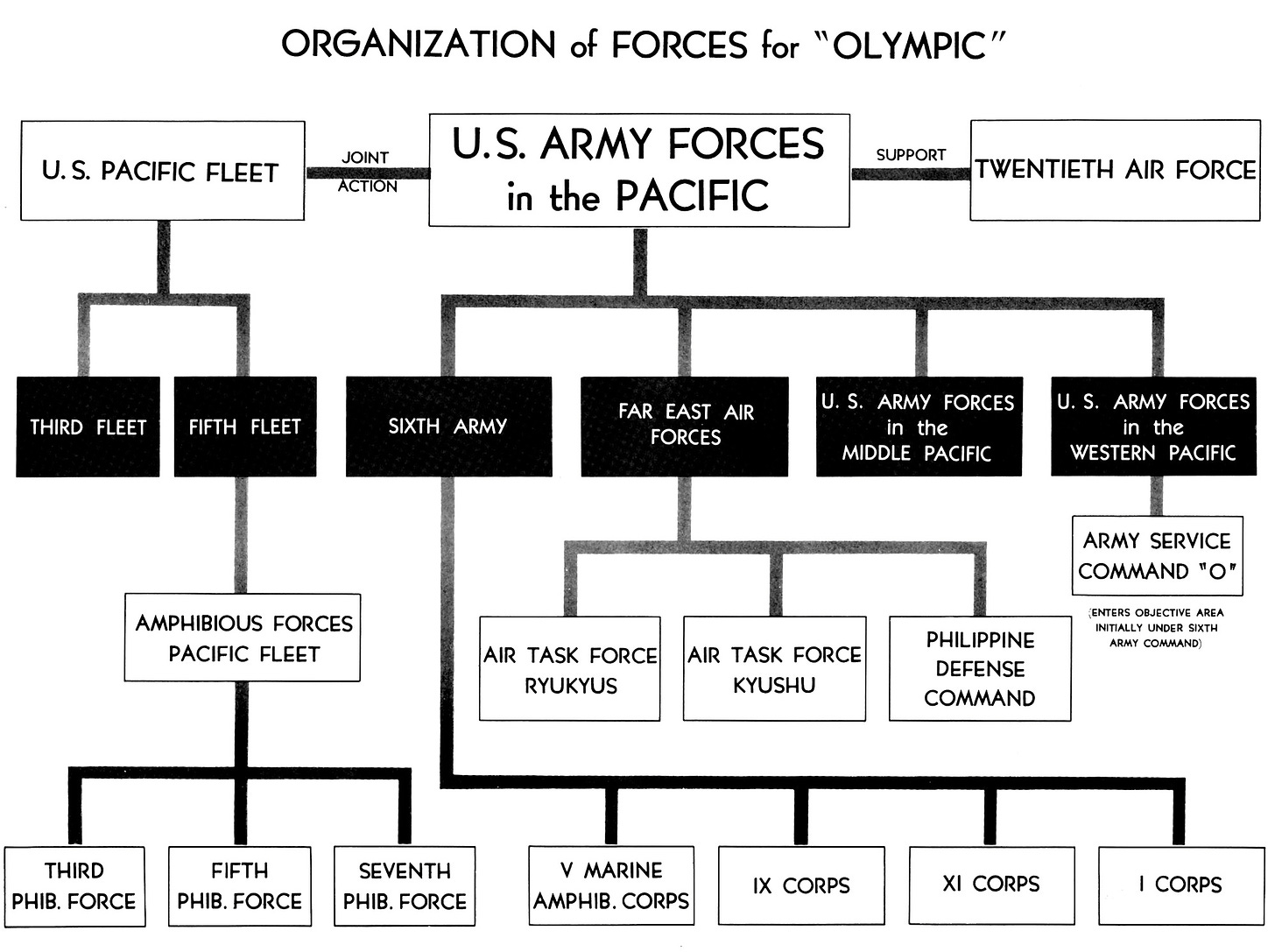

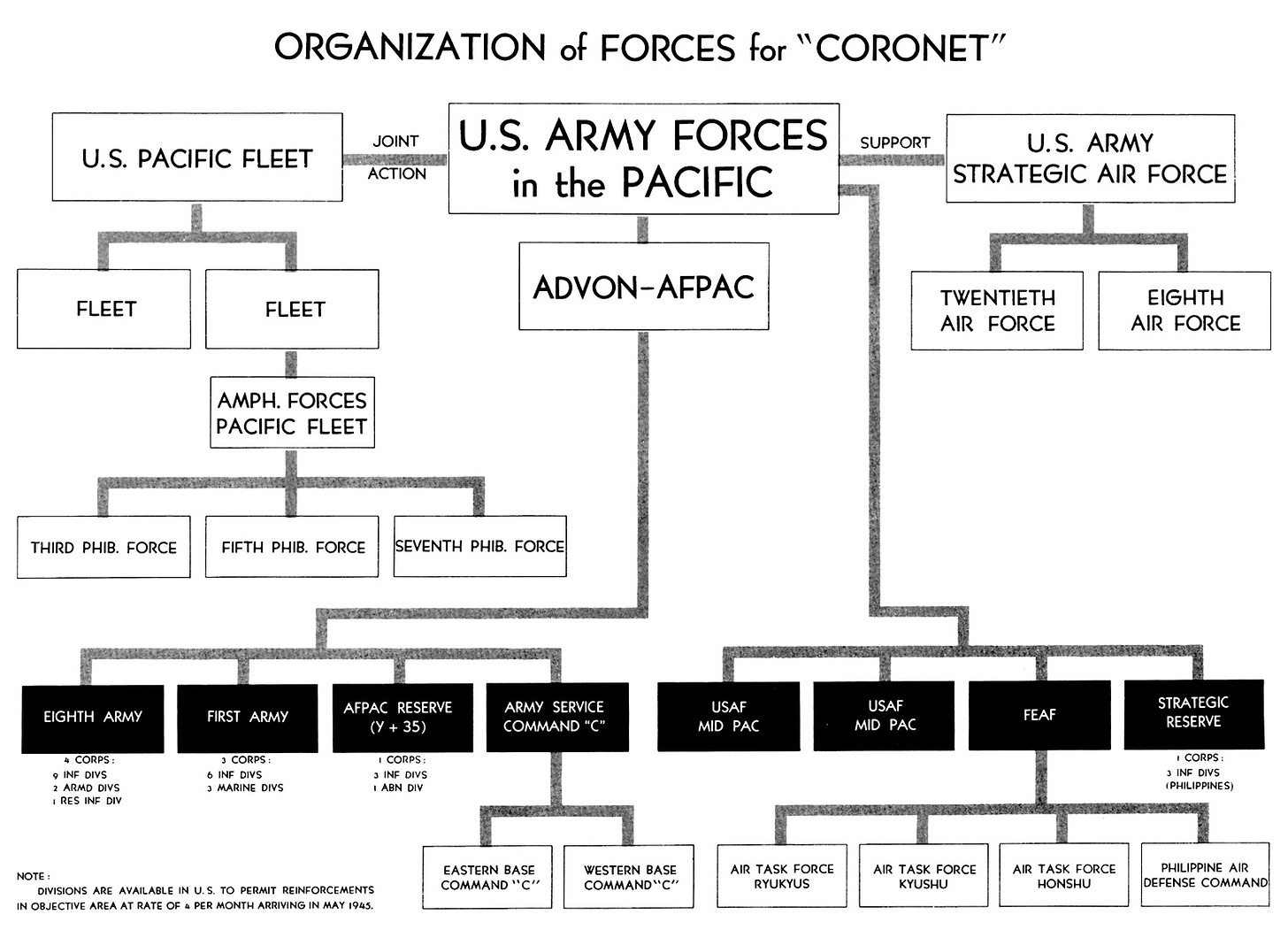

The operation had two parts: Operations Olympic and Coronet.

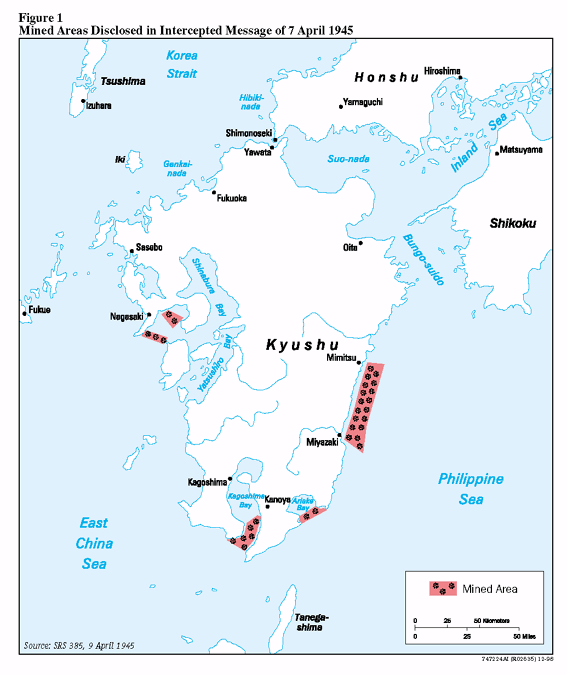

Set to begin in November 1945, Operation Olympic was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island, Kyūshū, with the recently captured island of Okinawa to be used as a staging area.

Later, in the spring of 1946, Operation Coronet was the planned invasion of the Kantō Plain, near Tokyo, on the Japanese island of Honshu.

Airbases on Kyūshū captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet.

The most troubling aspect of Downfall may have been the logistical problems facing military planners.

By 1945, there simply were not enough shipping, service troops, or engineers present to shorten the turnaround time for ships, connect the scattered installations across the Pacific, or build facilities like air bases, ports, and troop housing.

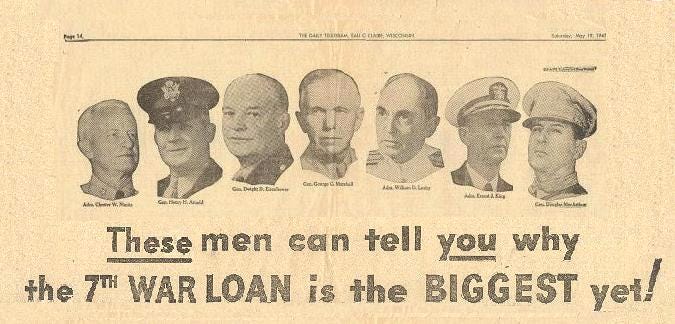

By this point in the war, the War Department had several military leaders that the government trusted to execute a quick end to hostilities.

Unlike the heavy political influence found in today’s wars, these men were given almost total freedom to plan large-scale military operations – Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bombs notwithstanding.

Six men of destiny

Responsibility for planning Operation Downfall fell to some of the most prominent American military leaders of the 20th century: Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff—Fleet Admirals Ernest King and William D. Leahy, along with Generals of the Army George Marshall and Hap Arnold, who commanded the U.S. Army Air Forces.

These six men, raised in the relatively stable and predictable world of late 19th-century small-town America, carried with them the values instilled by that era.

Arnold and MacArthur were West Point graduates; King, Leahy, and Nimitz came out of the Naval Academy; while Marshall honed his discipline at the Virginia Military Institute, a school renowned for its toughness, even more so than the service academies.

For these leaders, the concepts of duty, honor, and country were more than just words—they were guiding principles.

They approached their roles without a trace of cynicism, supremely confident in their ability and, crucially, their God-given right to steer the course of history, especially in the chaos of war.

King

Admiral Ernest King was a Navy man through and through.

As biographer John Skates noted, King had little time for anything beyond the service—his dedication was almost monastic, a lifelong commitment to the Navy.

But King was no ordinary warrior monk.

Humility wasn’t in his repertoire. Instead, he was a striking figure—handsome, arrogant, intelligent, stubborn, and ambitious.

Yet, these qualities came with a darker side: he was also profane, petty, rude, and by many accounts, the most disliked Allied leader of World War II.

Despite his flaws, King’s aggressiveness and willingness to take risks made him the kind of fighting admiral the Navy needed after Pearl Harbor.

His confidence and audacity were essential to the Navy’s resurgence. King brought a wealth of experience to the table—he served on submarines, became a naval aviator at 47, commanded naval air forces, and led aircraft carriers.

On the job, he was all business, with a reputation for being “meaner than I can describe,” as one staff member put it.

By mid-1944, as the Allies debated Japan's defeat, King’s stance was clear. True to his naval roots, he advocated for a blockade, arguing that Japan’s status as an island nation made it particularly vulnerable to such a strategy.

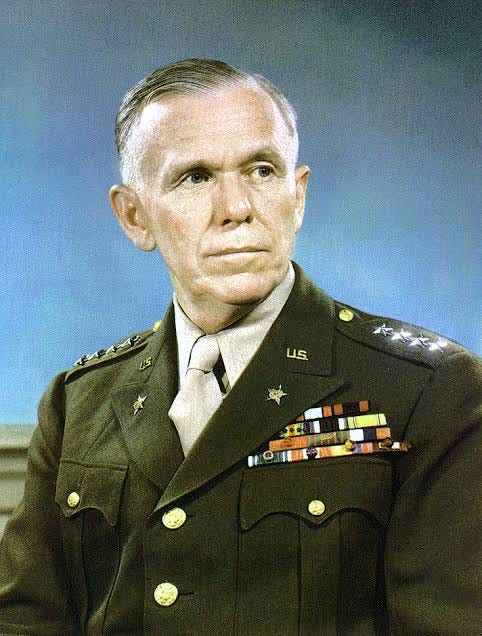

Marshall

Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall was a man defined by a core set of values: honor, integrity, self-denial (what we would call Stoicism today given its recent resurgence), discipline, and duty.

These principles weren’t just words to him—they were his guiding compass.

A staunch Europe-first advocate, Marshall had little patience for personal favors or special requests. When a Senator once asked him to promote a friend, Marshall’s response was blunt: “Mr. Senator, the best service that you can do for your friend is to avoid any mention of his name to me.”

Focused on the European front, Marshall largely sidelined the Pacific theater from 1942 to 1944.

His priority was Europe, and as one of the key architects behind the D-Day invasion of Normandy, he was singularly focused on achieving victory there.

However, when the time came to address Japan’s defeat, Marshall’s strategy was clear and decisive: he pushed for a full-scale ground invasion of the Japanese home islands.

In his view, a naval blockade would drag the war out indefinitely, risking the patience and support of the American public for the Pacific campaign.

Leahy

Admiral William D. Leahy was a battleship man through and through. Skeptical of airpower, he often viewed the claims made by airmen as inflated.

His expertise lay in ordnance and gunnery, the core of traditional naval warfare.

Leahy despised flying and preferred to move by ship or train, reflecting his old-school naval roots.

During World War II, Leahy held a rare and principled stance—he believed that strategic bombing was immoral, arguing that true warriors should never wage war on civilians.

He was especially horrified by the use of atomic bombs, fearing that it would lower the United States to the level of Dark Ages barbarians.

In his view, these new weapons of mass destruction represented a barbarism unworthy of a civilized nation.

Leahy was convinced that a naval blockade alone could compel Japan to surrender unconditionally, a reflection of his deep-seated belief in the power of traditional naval strategy over the emerging dominance of airpower and atomic warfare.

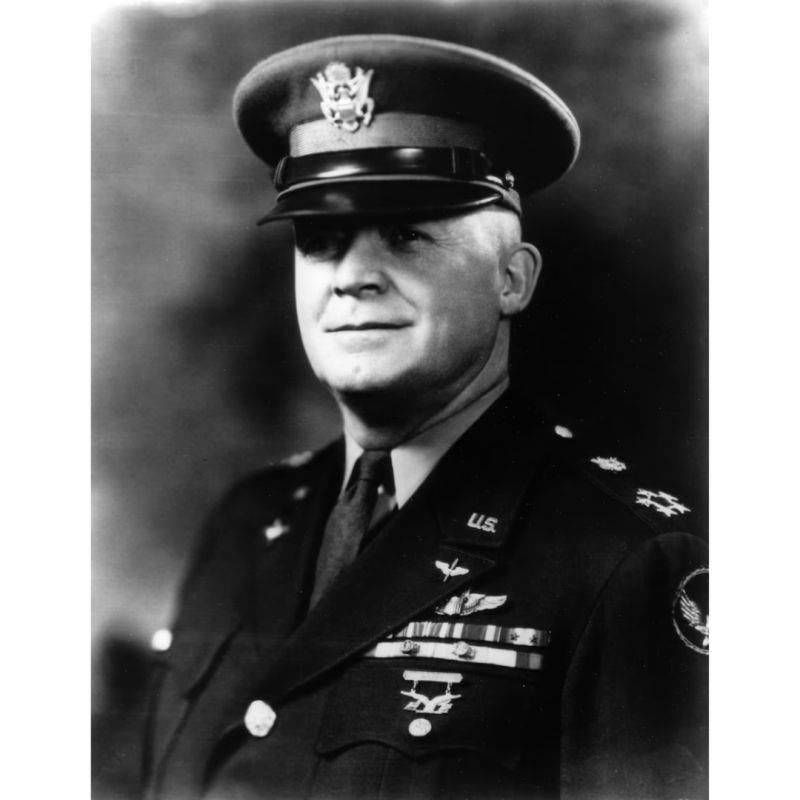

Arnold

Henry “Hap” Arnold found himself in a unique situation during World War II.

As the chief of the Army Air Forces, he was technically a subordinate to General George C. Marshall. But the Air Forces, with its specialized missions, distinct structure, and reliance on cutting-edge technology, operated with a level of autonomy that made Arnold more of an equal than a subordinate.

Arnold foresaw the future clearly, predicting that the Air Force would eventually become its own branch—a vision that materialized on September 18, 1947.

Despite his foresight and the growing independence of the Air Forces, Arnold had no issue reporting to Marshall. He held Marshall in high regard, recognizing in him a shared commitment to professionalism and duty.

Both men harbored a deep suspicion of the U.S. Navy, particularly of Admiral Ernest King, whose aggressive tactics often clashed with their own views.

Arnold’s aviation roots run deep—he received his pilot training directly from Orville and Wilbur Wright.

With this background, he firmly believed that the B-29 bomber could bring Japan to its knees, eliminating the need for a costly invasion.

Arnold argued that dropping over a million tons of conventional bombs would force Japan into an unconditional surrender.

And if it didn’t, he assured, it would at least make the invasion far easier.

As history shows, Arnold’s prediction was spot-on. The B-29 did indeed end the war, with the Enola Gay—one of his prized bombers—playing a pivotal role in bringing the conflict to a devastating conclusion.

Nimitz

Admiral Chester Nimitz stood in stark contrast to his direct superior, the brash Admiral Ernest King, and the famously self-centered General Douglas MacArthur.

Nimitz was the epitome of calm and approachability. He was known for giving his staff the freedom to make decisions, often valuing their advice over imposing his own will.

A true leader, Nimitz shielded his commanders from the pressures of higher headquarters, allowing them to focus on their missions without unnecessary interference.

Outside of his duties, Nimitz was a man of simple pleasures. He had a genuine love for children, kept a dog by his side throughout the war, and shunned personal publicity, preferring to let his actions speak for themselves.

When it came to strategy, Nimitz and his naval commanders favored a blockade to force Japan’s surrender.

He was a realist, understanding the potential need for invasion but always hoping it would remain just a contingency.

MacArthur

General Douglas MacArthur was a figure as complex as he was controversial.

Countless books have tried to capture the essence of the man, but in 1945, at age 65, he remained an enigma.

By that time, he had already spent decades as a general officer, but it was the disastrous fall of the Philippines in 1941 and 1942 that left him deeply bitter and distrustful of the U.S. Navy.

To his dying day, MacArthur believed the Navy had abandoned the Philippines, convinced that they could have reopened supply lines to the islands but chose instead to conserve their resources in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor.

In the final strategic debate of World War II—whether to invade Japan’s home islands—MacArthur was unwavering. He was not just in favor of an invasion; he advocated for the largest amphibious assault in history: Operation Downfall.

MacArthur’s vision was nothing short of grandiose and Downfall was largely his creation.

Throughout the Pacific War, the Allies struggled with the absence of a single Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C).

Command was fractured into regions: by 1945, Chester Nimitz was the Allied C-in-C for the Pacific Ocean Areas, MacArthur held the title of Supreme Allied Commander for the Southwest Pacific Area, and Admiral Louis Mountbatten was Supreme Allied Commander for South East Asia Command.

However, the looming invasion of Japan demanded unified leadership. Inter-service rivalry nearly derailed planning, with the Navy pushing for Nimitz and the Army insisting on MacArthur.

In the end, a compromise was reached. The Navy conceded, at least partially, and it was agreed that MacArthur would take total command of all forces if the situation required it.

Redeployment from Europe

Even though Sergeant Hale had come to Europe as a replacement in early September ‘44 to the 28th Infantry Division, he had still seen his share of combat.

Just not as much as some of the guys who had been here since the beginning…

On Aug. 29, 1944, the 28th ID had the honor of being the first American division to parade through Paris.

“Oh, what a feeling that must have been!” Hale thought.

He was bitter to have missed it.

Regardless, he had been with the 28th long enough to have breached the formidable Westwall of the German defenses in September 1944.

It was only a few months ago that the 28th ID crossed the Rhine and took positions in the Ruhr Pocket to stop any German forces driving south.

Then the Germans surrendered.

Now, Hale’s unit was being eviscerated – not by Nazis, but by paperwork. Seasoned troops were rotating out with slots being filled by green replacements. Unfortunately for Hale, his low points meant that he would be one of the soldiers redeployed to Japan.

One of the replacements, a man they called “Cherry”, came up to Hale now.

“Hey Sarge, there’s talk of our unit redeploying to Pearl and then Okinawa. Have you heard anything?”

Hale gave the young private a long look and then fished a German cigarette out of his cargo pocket. “Who do I look like, Cherry, Ernie Pyle? I don’t have any news.”

Despite being only a year or two younger than himself, Cherry’s youthful enthusiasm annoyed Hale.

Oblivious to Hale’s subtle body language that he’d rather be alone, Cherry went on, “Well, Sarge. I’m dying to kill some Japs.”

Hale chuckled, “I know private, that’s all you beat your gums about. Don’t worry, you’ll get your fill soon enough.”

Sergeant Hale walked off to find a matchbook and cast a glance back at Cherry…

Poor, stupid kid.

I had so many close calls with death over the past year, that I don’t think I have any lives left. Besides, even an ally cat with nine lives can have a bad day and get hit by a Buick.

Hale didn’t have the heart to tell the kid how he really felt, but he couldn’t shake the sense of dread that’s been with him since Hitler offed himself.

If we go to Japan, we’re all going to die.

Four days after D-Day, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall stood on the Normandy beaches, deep in conversation with First Army Commander Omar Bradley.

The topic turned to what lay beyond Europe.

Bradley, eager for the next fight, asked Marshall for a role in the Pacific once the war in Europe ended.

Just days later, George Patton made a similar request—he was willing to take any command, even a division, for the chance to battle the Japanese.

For the generals, the war wasn’t over. But for the average soldier, the prospect of finishing in Europe was clouded by the looming threat of redeployment to the Pacific.

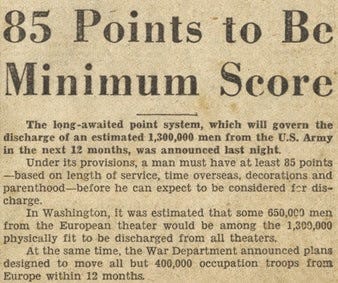

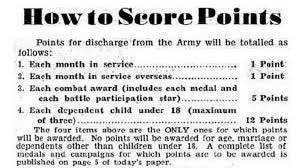

To manage this, Secretary of War Henry Stimson created a point system to determine which soldiers would come home and who would be sent to the Pacific.

Soldiers received points for various actions and activities. The more points a soldier accumulated, the sooner they were eligible to return to the United States.

Soldiers received one point per month of service and an extra point for each month served overseas.

They also earned five points for each campaign, a medal of valor or merit, or a Purple Heart.

Soldiers with dependents received 12 points per child, up to a maximum of three children.

Initially, soldiers needed 85 points to be eligible for demobilization. However, the threshold was later lowered to 50 points, making nearly a million more soldiers eligible and causing transport bottlenecks.

Qualifying scores for medical personnel varied by department. For example, the Medical Corps required 85 points, the Medical Administrative Corps required 88 points, and the Nurses Corps required only 71 points.

On V-E Day, 3 million American troops were stationed in Europe, with more replacements en route.

Based on the points system, the Army and Army Air Force units in Europe were divided into four categories for occupation, redeployment, or demobilization:

Category I: Units remaining in Europe. The occupation force for Germany, comprising eight divisions and 337,000 personnel, would be reduced further by June 1946.

Category II: Units headed to the Pacific. About one million soldiers, including 13 infantry divisions, 2 armored divisions, and 200,000 Air Force personnel, were slated for redeployment. Of these, 400,000 would go directly from Europe to the Pacific between September 1945 and January 1946. Another 400,000 would undergo retraining stateside, arriving by April 1946.

Category III: Units to be reorganized and retrained before being reclassified into Category I or II.

Category IV: Units returning to the U.S. for inactivation and discharge. This included 2.25 million soldiers eligible for discharge under the point system by the end of 1946.

The process of sending soldiers home by units triggered a massive reshuffling to place those eligible for demobilization into the appropriate groups.

Sergeant Hale’s unit, the 28th Infantry Division, saw a 20 percent turnover in enlisted men within a week and a 46 percent turnover in officers in just 40 days, destroying unit cohesion and efficiency.

Morale plummeted across European and Mediterranean units.

One general staff officer bluntly observed that Japan’s surrender “saved our necks.”

The planned invasion of Japan would have seen poorly prepared American forces, barely more seasoned than the green Japanese troops they would face, haphazardly thrown together, and expected to operate as a team.

In other words, the invasion of Japan would not be performed solely by battle-hardened troops eager to finish the fight.

As a former infantryman with the 101st Airborne, I can tell you that training and fighting with the same unit over months and years results in an invaluable battlefield advantage.

We anticipate each other’s movements and commands. There’s a subtle shorthand that develops and an efficiency gain that is simply lost when you smash units together like a chef’s salad.

The outcome of the invasion of Japan could have been far more disastrous than anyone anticipated.

The Invasion Plan, Olympic

Operation Downfall, the Allied plan to invade Japan, was divided into two major phases.

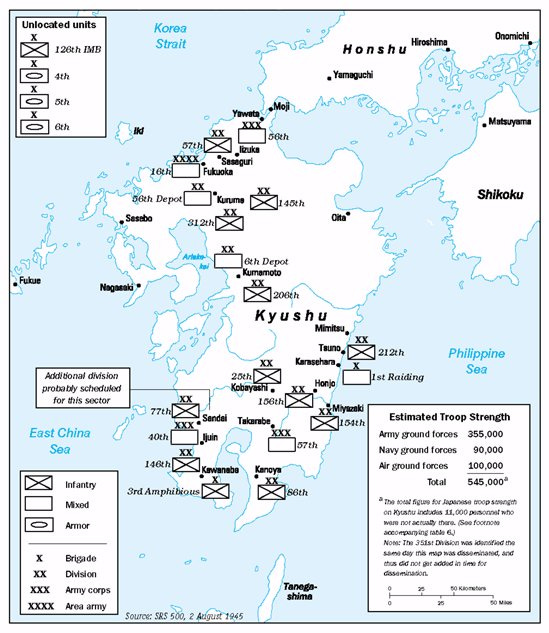

The first, Operation Olympic, focused on invading Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s four main islands.

Success there would pave the way for Operation Coronet, the decisive strike on Tokyo and the surrounding area of Honshu.

The initial assault, scheduled for X-Day on November 1, 1945, was expected to kick off an 18-month campaign, stretching into May 1947.

To understand the scale of this operation, consider the staggering number of civilian casualties from strategic bombing during World War II—ranging from 90,000 to 146,000 in Hiroshima alone.

The projected civilian toll from Operation Downfall, if it had gone forward, would have been in the tens of millions.

The Allied naval force assembled for the invasion would have been the largest in history, comprising 42 aircraft carriers(!), 24 battleships, and 400 destroyers and destroyer escorts.

The land invasion would involve all 21 U.S. Army and six Marine Corps divisions in the Pacific, supplemented by five armored and 13 infantry divisions from Europe.

Additionally, a British Commonwealth corps of five divisions would operate under American command as part of Coronet.

Operation Olympic would begin with a three-pronged assault on southern Kyushu, led by Admiral Raymond Spruance and the U.S. Navy Fifth Fleet.

The preliminary assault would involve a massive lift capacity to transport 12 divisions—originally planned for eight—consisting of 33,000 personnel and 50,750 tons of equipment each, across more than 1,300 ships.

The fleet would include 20 amphibious force flagships, 210 attack transports, 12 transports, 84 attack cargo ships, 92 high-speed transports, and over 900 landing ships of various types.

Air support would come from more than 1,900 planes launched from 22 U.S. Navy carriers, alongside 10 carriers from the British Royal Navy.

Eight additional escort carriers from the Royal Navy and eight more carrying Marine Corps ground support aircraft would also participate.

General George Kenney’s Far Eastern Air Force, with over 2,800 aircraft, would provide additional air cover and support the landings. Naval gunfire from over 2,700 ships would further bolster the invasion force.

The B-29 bombers of the 20th Air Force, under Lieutenant General Nathan Twining, would continue to target strategic objectives but were prepared to shift their focus to direct support of Operation Olympic if required.

Olympic was not designed to capture all of Kyushu, only its southern third, which would serve as a staging ground and airbase for Operation Coronet.

Once the initial objectives were secured and troops began advancing northward, engineers from all services would construct airfields, ports, and other necessary infrastructure to support the final push toward Tokyo in the second phase of Operation Downfall.

MacArthur was particularly optimistic about casualty estimates. In preparation for a briefing between President Truman and General of the Army George C. Marshall regarding the invasion, MacArthur sent over his casualty estimates:

“…a total of 95,000—dead and wounded—for the expected 90-day campaign to seize the southern half of Kyushu.” He also estimated 50,800 for the first 30 days.

Marshall was flabbergasted. How could MacArthur come up with such a low number? Was it just blind optimism?

Marshall sent a message back:

“The President is very much concerned as to the number of casualties we will receive in the Olympic operation. This will be discussed with the President about 3:30 PM today Washington time. Is the estimate given in your [message] of 50,800 for the period of D to D+30 based on plans for medical installations to be established or is it your best estimate of the casualties you anticipate from the operational viewpoint. Please rush answer.”

Two other documents pertaining to the casualty estimates were prepared for Truman. One put the casualties as high as 220,000; the other said casualties would be closer to those suffered in the invasion of Luzon—31,000.

How were the two casualty tables so wildly different?

The first used broad experience and objective criteria as its guide. The second simply reflected MacArthur’s view of casualties as a U.S.-to-Japanese kill ratio and included considerations of the casualty rate from Normandy.

After receiving some criticism, MacArthur revised his casualty numbers for the President: In it, MacArthur estimated that in the landing and three months of fighting on Kyushu, 94,250 men would be killed or wounded in battle, and another 12,600 would be felled by disease and accidents—a casualty total of 106,850.

To many of MacArthur’s peers, these numbers were far too low given the task ahead of them.

Operation Coronet

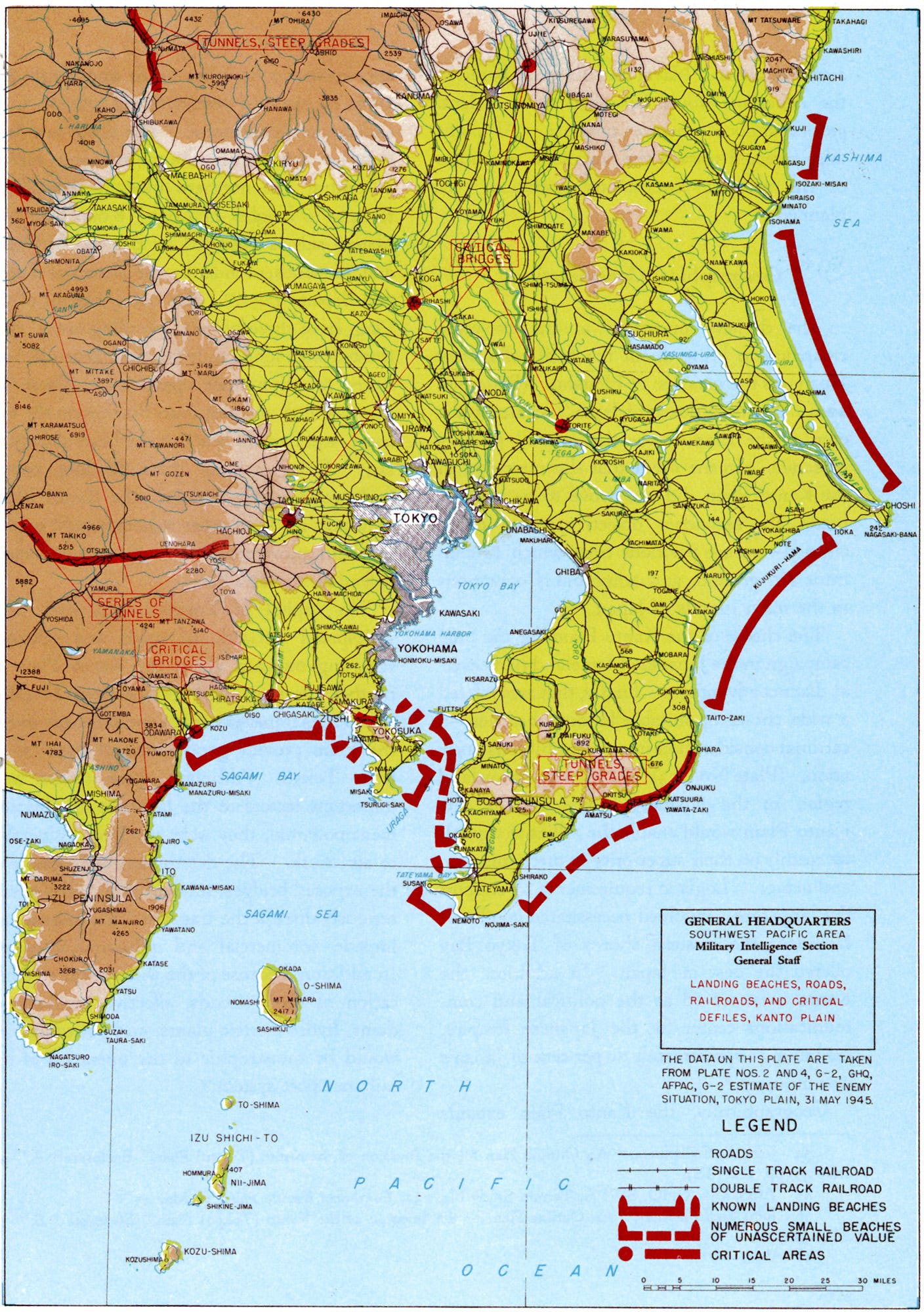

Assuming everything went according to plan and air bases were established to support further operations, Operation Coronet was tentatively set to begin on Y-Day, March 1, 1946.

The target: the Tokyo Plain, a 5,500-square-mile area that was not only the heart of Japan’s government and communications but also home to half of its defense industry.

The region boasted Japan’s best port facilities, offered numerous landing beaches, and, crucially, provided ample space for American mechanized and armored forces—something that had been sorely lacking throughout the Pacific War.

Coronet’s battle plan was ambitious.

The US Eighth Army, led by Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger, would strike through Sagami Bay with three corps: X Corps, under Major General Franklin C. Sibert; XIV Corps, under Lieutenant General Oscar W. Griswold; and XIII Corps, with the 13th and 20th Armored Divisions from Europe, under Lieutenant General Alvan C. Gillem.

Simultaneously, the U.S. Tenth Army, commanded by General Joseph W. Stilwell, would attack from the east, advancing along the Boso Peninsula.

This force would include the III Marine Amphibious Corps—comprising the 1st, 4th, and 6th Marine Divisions under Lieutenant General Roy Geiger—and XXIV Corps, with three infantry divisions led by Lieutenant General John R. Hodge.

The objective for both armies was clear: isolate and capture Tokyo.

In reserve, General Courtney H. Hodges’ U.S. First Army, consisting of one airborne division and ten infantry divisions, would remain ready to deploy.

Additional American divisions could be called in from the United States or Europe as needed, with up to four arriving each month.

Facing the Allies on Honshu were the Japanese Eleventh, Twelfth, Thirteenth, and Fifteenth Armies, totaling over 40 infantry and armored divisions, plus naval and air personnel repurposed as ground troops.

Intelligence suggested that Japan’s air force, including kamikazes, would be severely depleted after defending against Operation Olympic, leaving perhaps only 2,000 aircraft to oppose Coronet.

Senior U.S. ground commanders were confident that taking Tokyo would force Japan into unconditional surrender.

However, if resistance continued, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had contingency plans for up to 22 divisions to engage Japanese forces west and north of Tokyo, with operations slated to begin around July 1, 1946.

Casualties

Haruko sat near the cliff’s edge and gazed at the impossible number of American ships on the horizon.

They were coming to her home. Her island. Okinawa.

The relentless bombardment never ended. Did the Americans have an infinite number of munitions?

The sound was constant and deafening.

After she had finished her ritual reading of the emperor’s declaration of war rescript, she resolved to compose one final Haiku before she chose gyokusai – “to die gallantly as a jewel shatters.”

She took a deep breath and closed her eyes.

“Cherry blossoms fall,

Waves of steel crash on our shores,

I choose the quiet.”

Her nose crinkled. Not her best work – her father would surely disapprove. But he was with his ancestors now, as she would be soon.

The commander had given her and everyone in her village two hand grenades. “The divine emperor directs you to throw one of them at the enemy and the other to engage in gyokusai,” the commander had said.

But Haruko did not want to kill – she just wanted this madness to end. She chose instead to throw her body off the cliff closest to her house, where she used to watch the sunrise with her older brothers.

She thought again of the commander’s words, “The Americans will cut off your noses, your ears, and chop off your fingers. You must not allow yourselves to be captured.”

Haruko gave one last thought to her name – 春子 meaning the “Spring Child.” How beautiful it was that she was born in the spring, and will die in the spring.

She stood up from her kneeling position and walked to the edge of the cliff.

Without any further words or ceremony, she stepped off… and finally experienced the quiet.

No one harbored any illusions that the invasion of Japan would be anything but brutal.

The Pacific Theater had already proven to be a grinding, unforgiving battleground, and there was little reason to believe the fight would ease up when it came to the Japanese home islands.

Unlike the Western Front in Europe, where tens of thousands of Germans surrendered rather than fight to the bitter end, American planners anticipated a level of resistance in Japan that would make every previous battle seem tame by comparison.

The ferocity of Japanese defense had been demonstrated time and again.

In November 1943, the Second Marine Division endured 3,381 casualties in just 76 hours at Tarawa, where nearly all 4,836 Japanese defenders perished, with only 17 survivors.

Ten months later, the First Marine Division suffered 6,526 casualties, while the Army’s 81st Infantry Division took another 1,393 at Peleliu.

Out of a garrison of 10,900 Japanese troops, only 19 were captured alive.

The toll in the Philippines was staggering as well.

The U.S. Sixth Army sustained nearly 41,000 casualties during the Luzon Campaign, while the U.S. Eighth Army endured 12,000 during the Visayan-Southern Islands Campaign.

At Iwo Jima, the Fifth Amphibious Corps saw 25,000 killed and wounded, and on Okinawa, the Tenth Army suffered almost 40,000 casualties.

Japanese losses were even more devastating: 242,000 killed in the Philippines, over 21,000 on Iwo Jima, and more than 110,000 on Okinawa.

By this point in the war, the Japanese armed forces were more like a World War I-era army with medieval undertones - but the Japanese repeatedly displayed a staggering capacity for resistance, with most preferring death over capture.

By April 1945, the Joint Chiefs of Staff calculated that the daily casualty rate in the Pacific was 7.45 per thousand, compared to 2.16 in Europe.

The battles had been bitter across the Pacific, but none more so than Okinawa, where U.S. casualties hit 35 percent.

The 29th Marine Regiment alone suffered an 80 percent casualty rate—the highest for any American regiment since the Civil War. And as planners soon realized, Kyushu's terrain bore an uncanny resemblance to Okinawa's.

Admiral King optimistically predicted that casualties during Operation Olympic would mirror those on Luzon and Okinawa—around 40,000.

However, ground force planners were far less optimistic.

Despite MacArthur’s optimistic estimates, General Marshall warned Truman that Allied losses could easily reach 500,000, and after the war, Omar Bradley suggested it could have been as high as one million.

The Japanese, meanwhile, were fully prepared for a fight to the death.

The most diehard elements counted on a force of 2.35 million soldiers, bolstered by 4 million army and navy civilian employees, and a 28-million-strong civilian militia, armed with everything from muzzle-loading rifles to bamboo spears and bows.

For many Japanese civilians, the prospect of the invasion was terrifying. One high school girl, Yukiko Kasai, was issued an awl and instructed, "Even killing one American soldier will do. ... You must aim for the abdomen.”

Operation Ketsu-go

The U.S. had been cracking Japanese communications under the Ultra-Magic operation, revealing Tokyo’s preparations as the U.S. invasion loomed.

As Nazi Germany neared collapse, the Japanese Army General Staff sent a telling message to their military attaché in Lisbon, urging detailed reports on the German resistance.

The goal? To use these insights to bolster Japan's own "decisive battle" at home, training special guard units and citizen volunteers to defend the homeland at all costs. Japan's leadership was resolute—they would fight to the bitter end.

Specifically, the Japanese asked that the “battle of resistance” in Germany “be reported as fully as possible in order to furnish reference material for the decisive battle in our homeland and particularly for the training of special guard units and citizens’ volunteer units. ... In this way, we shall make firm our determination to defend the capital to the bitter end.”

Magic wasn’t just eavesdropping on military chatter.

Diplomatic cables from neutral observers in Japan, offering a more impartial view, were also being intercepted.

The Portuguese Minister in Japan reported that Japan was fortifying its coasts and mountains, mirroring Germany’s futile resolve to continue the war despite no chance of victory. He noted a Japanese national guard being organized to wage guerrilla warfare against invaders.

Similarly, a message from the Swiss Minister in Tokyo captured Japan's strategy of prolonging the war, hoping to exhaust its enemies – saying Japan “is still hoping to escape [defeat] by prolonging the war long enough to exhaust [its] enemies. Many eagerly desire the landing of the Americans in Japan proper, since they think it would be the last chance to inflict upon the Americans a defeat serious enough to make them come to terms.”

So, some Japanese welcomed the idea of a U.S. landing, believing it could provide the last chance to strike a devastating blow, forcing the Americans to negotiate.

This strategy was the essence of Operation Ketsugō, or "Operation Codename Decisive," Japan’s last-ditch plan to defend the home islands.

A central element of this defense was the kamikaze or suicide planes. In addition to their remaining fighters and bombers, the Japanese reassigned nearly all their training aircraft for kamikaze missions.

By July, the Japanese army and navy had over 10,000 aircraft prepared, with more expected by October, and they planned to throw nearly all of them at the invading Allied fleets.

During the Battle of Okinawa, fewer than 2,000 kamikaze planes had launched attacks, achieving roughly one hit for every nine attempts.

But at Kyushu, the Japanese anticipated better results due to more favorable conditions, including terrain that could diminish the Allies’ radar advantage.

They aimed to increase their success rate to one hit for every six attacks by launching a massive, coordinated wave of kamikazes. The Japanese estimated these strikes could sink over 400 ships.

By focusing on troop transports rather than carriers and destroyers, they hoped to inflict far greater casualties than they had at Okinawa.

In fact, one study suggested that kamikazes could destroy up to a third or even half of the invasion force before they reached the beaches.

Japan’s remaining major warships included four battleships, five aircraft carriers, two cruisers, 23 destroyers, and 46 submarines—all of which were damaged.

However, due to fuel shortages, the Imperial Japanese Navy did not plan to send these ships into open battle again. Instead, they would be stationed at port, using their anti-aircraft firepower to protect naval installations.

Japan’s defense also relied on smaller, more expendable vessels. This included around 100 Kōryū-class midget submarines, 300 smaller Kairyū-class midget submarines, 120 Kaiten manned torpedoes, and 2,412 Shin'yō suicide boats.

Unlike the larger ships, these small craft, along with the destroyers and fleet submarines, were expected to play a significant role in the coastal defense.

Their mission: destroy approximately 60 Allied transports, aiming to disrupt the invasion force before it could establish a foothold on Japanese soil.

As has been reported many times before, the U.S. manufactured numerous Purple Heart medals, the award for those wounded or killed while serving.

In all, approximately 1,531,000 Purple Hearts were produced for the entire war effort with a full 500,000 produced for Operation Downfall.

Despite wastage, pilfering, and items that were simply lost, the reserve of decorations stood at approximately 495,000 after the war – according to the Truman Presidential Library.

Interestingly, the U.S. ordered 34,000 more of them after the Vietnam War, but the medals from 1945 are still updated and issued as needed.

Strictly speaking, a modern Purple Heart recipient may never know for which war their medal was made since the minute differences are indistinguishable unless examined by an expert.

Chemical Weapons

Japan’s geography and predictable wind patterns made it particularly vulnerable to gas attacks, a fact that did not go unnoticed by American planners.

Such attacks could have been devastating, especially given the Japanese tendency to use caves as defensive positions, where gas would be most effective.

Although chemical warfare had been outlawed by the Geneva Protocol, neither the United States nor Japan were signatories at the time.

The U.S. had pledged never to initiate gas warfare, but Japan had already broken that moral barrier by using gas against Chinese forces earlier in the war.

The U.S. death toll was inciting strong reactions. "You Can Cook Them With Gas," read an editorial headline in The Chicago Tribune on 11 March 1945, as U.S. troops were fighting on Luzon and Iwo Jima with heavy losses.

Major General William N. Porter, chief of the Army's Chemical Warfare Service, orchestrated a scheme to kill an estimated five million Japanese with poison gas.

According to the U.S. Naval Institute, a document kept under wraps for five decades, the 29-page, "A Study of the Possible Use of Toxic Gas in Operation Olympic," details the ultimate attack.

“Strategic bombers (B-29s and B-24s) would drop 56,583 tons of poison-gas bombs in the first 15 days of what the document called the "initial gas blitz." And they were to drop another 23,935 tons of gas bombs every month that the war dragged on or until all targets had been hit.”

When landings began in November, tactical fighters and attack planes were to drop another 8,971 tons in the first 15 days, followed by 4,984 tons of bombs every 30 days.

Other planes would swoop low, using spray tanks to spread thousands of tons of liquid poison over Japanese defenders.

According to the report, Japanese cities were particularly vulnerable to gas attacks, notably because residential areas were constructed almost entirely of wood, and "Liquid mustard [gas] is readily absorbed by wood which is almost impractical to decontaminate."

The planning for these chemical attacks began as early as 1943, after nearly 1,000 U.S. Marines were killed taking Tarawa Atoll from fanatical Japanese defenders.

In 1944, Ultra intelligence revealed that the Japanese themselves doubted their ability to respond to a U.S. gas attack.

Japanese commanders were explicitly warned, "Every precaution must be taken not to give the enemy cause for a pretext to use gas."

Such was their fear of escalation that Japanese leaders were prepared to overlook even isolated tactical use of gas by U.S. forces on the home islands to avoid provoking a larger-scale chemical conflict.

Atomic Weapons and the Great Debate

The atomic bomb was no sure thing when it came to forcing Japan’s surrender.

Despite its unimaginable destructive power, the bomb was costly to produce and available in extremely limited numbers—only two were ready for use in August 1945.

If these hadn’t been enough to break Japan’s resolve, General Marshall had a contingency plan that involved using up to nine more atomic weapons, provided they could be produced in time.

Instead of strategic targets, these nine would be deployed tactically to support Operation Olympic. Unfortunately, Marshall’s tactical atomic bomb plans are difficult for researchers like myself to access, if they exist at all.

But there is still an ongoing debate about whether the U.S. could have won the war without atomic bomb usage.

A greater percentage of Americans than ever before now doubt the necessity of using nuclear weapons against Japan.

Some claim that there is historical evidence that Japan was on the brink of surrender at the moment when the bombs were deployed.

I remain skeptical.

All of my research indicates a Japanese public and military complex that was determined to fight to the last man, woman, and child.

Granted, the Soviet Union entering the war likely had a compounding psychological effect that together, with atomic bomb use, helped compel surrender. But there is no “historical evidence” that the Soviet Union alone was enough to force Japan’s capitulation.

This myth likely started in 1965, when historian Gar Alperovitz published a book that argued that the use of atomic weapons on Japanese cities was intended to gain a stronger position for postwar diplomatic bargaining with the Soviet Union, as the weapons themselves were not needed to force the Japanese surrender.

If that were true, and the U.S. won a “stronger negotiating position” by using the bombs, why was the settlement so disfavorable to the Western allies when dividing up Germany and Berlin?

Besides, the ultimate fate of Germany was largely decided by the “big three” allied powers a full seven months before the atomic bomb usage, at the Yalta Conference in February 1945.

In light of how close the U.S. came to chemical weapon use, the atomic bombs were a mercy by comparison.

Frankly, without the atomic bomb and the Soviet Union entering the war combined, it’s hard to see how anything short of a full-scale invasion would have compelled Japan to surrender.

And that invasion would have been unimaginably costly, with no guarantee of success.

Operation Coronet, the planned assault on Tokyo, could have easily turned into a brutal counterinsurgency—a type of conflict the United States hadn’t faced on a large scale since the wars against Native American tribes, and wouldn’t encounter again until Vietnam.

But history took a different turn.

The atomic bombs did their job. On September 2, 1945, the United States Navy sailed into Tokyo Harbor for Japan’s formal surrender.

The ceremony itself was a compromise between the Army and Navy, both of whom wanted the honor.

In the end, General MacArthur signed for the Allied Powers, and Admiral Nimitz signed for the United States, aboard the Navy battleship Missouri.

Even without Operation Downfall, World War II was the most devastating conflict in human history.

And the generation who fought in that war is passing at an increasing rate.

Resolve to seek out a World War II veteran and shake his or her hand.

These people are our last living connection to this conflict.

Be sure to subscribe to me at Eyes Only on Substack to receive more content like this, along with Ukraine War analysis and military technology.

Mahalo for your in-depth analysis

Thi ssubject is very for me. I'm an America of Japanese and Filipino ancestry, and my grandparents suffered and survived the occupation of the Philippines by the Imperial Japanese military

My heart breaks for the millions of Japanese non-combatant civilians killed by US strategic bombing, including the atomic bombs

But it also break for the tens of millions of non-combatant civilians killed by the Imperial Japanese military, peoples from Burma and Vietnam, to Korea and Manchuria, to Indonesia and Polynesia, and tens of millions in between. Peoples who were still fighting against Japanese Imperial occupation on the days of the atomic bombs

And your article is a sharp and necessary debunking of the myth that either Operation Olympic (or the alternative naval and air blockade) would have been any less bloody

The atomic bombs were horrible. But short of unconditional Japanese surrender prior to the bombs, no other alternative by the US government was better

Thank you,Wes. For years, I was disgusted that the US dropped the bomb, not once but twice, on civilian populations. This crystallizes the horrible decision facing Truman. I cannot imagine the courage that decision required.

After digesting this, there is no question that the bomb saved millions of lives by forcing the emperor to unconditional surrender. Truman may have been one of the top presidents of the 20th century. I was still tiny tot when he left office. All I knew of him for years was that he had the misfortune of succeeding FDR. And that he dropped the bomb.